Once again you have the option to listen or read. Either way, thanks for being here and I look forward to your comments and ideas.

The Solution to drug addiction is unlikely more drugs

Big Pharma was a Big Part of creating this crisis in the first place. At minimum it poured gasoline on a fire lit by the loss of religion, social and community connections. Yet of course Big Pharma has come up with "the solution", which is (surprise!) more drugs. Call me Mr. Suspicious-Pants, but I just don’t trust them. But, according to The Experts™, the best thing to do for narcotic addicts is to put them on Opioid Replacement Therapy (ORT) in Opioid Replacement Programs (ORP’s).

Methadone was the first drug used for ORT, and for many decades was the only show in town. Methadone is a once-a-day, slow-onset-slow-offset narcotic that does not give the “high” of other shorter-acting versions, and is thus felt to be less addictive. But like other narcotics, methadone still blunts emotion, saps energy, and likely causes increasing chronic pain over time through “receptor upregulation”. This phenomenon is known as narcotic-induced hyperalgesia.

As mentioned in part one, opioid replacement therapy is an odd name, as it implies that an addict’s problem is that he lacks opioids. But a few generations ago, the name made more sense. Those entering a methadone program would sign a contract. They agreed to stop using other drugs, and methadone replaced the drug they were giving up. Admission to the program, continued attendance, and continuing to receive methadone was contingent on adhering to the contract. If your urine spot-test was “dirty”, you were out. There were expectations and standards for those in the program. You weren’t free to use whatever drugs you wanted if you wanted to be in the program.

Freedom without responsibility = disaster

Circa 2012 I attended a large conference where a certified Harm Reduction Expert™ who ran a methadone clinic was asked what he did when a patient failed a spot test. His answer shocked me (and I should add - also those sitting around me). A dirty test was a failure of the program, not the individual, he explained. It was a sign that the dose was not high enough. If an addict was getting enough methadone, he wouldn’t be using other drugs in the first place. This was when it struck me that today’s ORP’s are not what I learned about in the 90’s, where contracts were strict, and tapering was de rigueur.

I’ve watched this idea that giving people drugs will somehow make them use less other drugs creep into medical practice. Circa 2021 I had an alcoholic patient come to ER in a very bad state. He had been to ER a couple of nights earlier and was given a prescription for a huge bottle of clonazepam. This is a benzodiazepine - a drug that some call “dehydrated booze”, which can be used to wean people off alcohol in inpatient settings. But because it’s effects overlap so much with alcohol, it is dangerous when used in combination. And that’s what this patient had done. Most of the bottle (enough for a big daily dose for a month or two) was already gone. The patient did survive. When I reviewed the previous notes, it was apparent that the patient hadn’t solicited the prescription. He hadn’t said anything about wanting to quit or taper. The physician thought that if the patient was taking clonazepam, he would drink less. Instead, he used both drugs, and nearly died.

As Dr. Julian Somers so eloquently talked about at FSIM 2023 (watch for an online Free Speech In Medcine event with him coming up soon), methadone programs used to be a PROGRAM with many facets - vocational training with a view to employment, counselling for mental health issues, reconnecting with family. The “active ingredients” were everything but the methadone. Now a methadone (or Suboxone) program is about getting a drug every day, and little or nothing else.

In a well written City Journal article , journalist Erica Sandberg describes her experience in San Francisco, posing as a drug addict who had just arrived from the midwest. Here is an excerpt:

In NS, as I’ll go into below, there are zero government-funded inpatient abstinence-based programs for narcotic abuse, and fewer inpatient options for alcoholics than in the past.

This time for SURE this is going to work

Recently methadone has mostly been replaced by Suboxone, which is a somewhat safer alternative that blocks opioid receptors in our brain and spinal cord, blunting withdrawal symptoms. And by happy coincidence it’s more expensive, generating a higher profit for Big Pharma. Experts™ explained to me that changing from methadone to Suboxone would cause overdose deaths to plummet. I think you can guess what has actually happened.

Although there is no doubt that both methadone and Suboxone can mitigate the cravings that withdrawal causes, they do nothing to address the root causes of addiction, and used alone they do nothing to help an individual move past addiction and into the sober, meaningful life that lies beyond.

The Abandonment of Abstinence as a North Star

Despite the failure of ORP’s, increasingly they are the only tool in the healthcare practitioner’s toolchest here in Canada (and elsewhere as I understand it).

Over the years, healthcare overlords have increasingly abandoned funding “abstinence-based” programs (ABP’s) - those that are focused on helping patients get off drugs rather than just replacing them with a (purportedly) less harmful alternative drug. Most ABP's also involve reintegrating into the community - be it through finding a job, having a sponsor in the community, reconnecting with family, finding a group home, a church, whatever. ABP’s are organized on the belief that sending a person directly back into the same environment and circumstances that stimulated him to be addicted in the first place will likely torpedo his chances of staying sober, even if we do give him methadone or Suboxone in an ORP.

Harm reduction including needle exchanges, supervised injection sites, shelters, ORP’s, and most recently “safe supply” - have replaced abstinence-based programs. These interventions are more left-brained and mechanistic, with no need to bring in all that controversial spirituality or (God forbid) religion which were the foundation of success in 12-Step programs. Governments appear to be “doing something” to fix addiction when they run harm reduction programs, while at the same time that the death toll increases.

These programs give hard data for proponents to use to argue that they are working. The number of needles you give out, or the number of people on methadone, the number of people “retained” in programs can easily be counted - very important for the bean counters that abound in our overly-bureaucratized healthcare system. But not everything that can be counted actually counts.

When travelling recently I picked up an old-fashioned local print newspaper. There was a front-page article announcing the fantastic successes and expansion of the local harm-reduction program. In the article, the director touted the number of patients on methadone and Suboxone, increased staffing at the centre, and the huge number of free needles they had given out in the prior year. More than the year before! Wow! The program was clearly a success!!

Not once in the article was there any mention of how many overdose deaths had occurred that year. I looked it up - it had increased greatly in that area. And not once was it mentioned how many (if any) of their clients had become abstinent, gotten off the street, or found jobs. Nowhere could I see evidence that this program had actually helped anyone in a meaningful way. And for anyone who walked around the city it was clear that the problems of homelessness and addiction had objectively worsened.

Thomas Sowell and others have talked about how government-funded programs, although often started with a noble goal in mind, quickly morph into entities that are mainly focused on their own survival, growth, and enrichment. Free needles and drug-free people are not the same target. Program directors and politicians patting themselves on the back for the former, while ignoring the latter as it worsens, is frustrating to watch, and a perfect demonstration of Goodhart’s Law.

Giving out drugs is lucrative

Doctors make BIG MONEY doling out daily doses of drugs such as methadone and Suboxone. This creates a perverse incentive where physicians want as many people on methadone and Suboxone as possible (cha-ching, cha-ching). I have had numerous addicts tell me that they asked to taper off their ORT, they have been directly told not to do so, because it would be “dangerous”.

I should mention that there are thousands of ex opioid addicts who strongly disagree with Dr. Henry’s view.

A doctor friend of mine took a methadone prescriber's course recently. Being logical, old-fashioned, and innocently naive to the new dogma in addiction medicine, she asked about tapering. The Expert™ running the program tut-tutted. You could never take an addict off methadone, she explained. "It would be like taking a diabetic off their insulin". She was told that addiction is a “lifelong disease” that can only be treated by "replacement" and “harm reduction”.

In many provinces, “addiction specialists” who run ORP’s are amongst the highest paid physicians. For instance, a CBC article from Newfoundland details how 2 of the highest 10 paid physicians in that province run methadone clinics. One bills 1.6 million dollars per year, the other “only” 1.2 million. This is many times more than a regular old family physician can manage to bill. It’s also far more than your neurosurgeon earns, and he trained for 8 extra years beyond med school and has to be prepared to get called in at 3AM to do a delicate emergency operation on your brain.

ABP’s are not a panacea, but they should be an option

Why were abstinence-based programs abandoned? Well, here’s my understanding. These programs are expensive. Many patients fail. Many relapse. Being sober is hard. Those who work in these programs are poorly paid for a difficult and emotionally taxing job. It’s much easier just to hand out ORT.

Currently if you are an addict in Nova Scotia and you want help, the only “help” I can get you is to refer you to start on ORP. And unlike something like cancer treatment or a referral to neurology, there is no wait to start on ORT.

On the other hand, if you want to get off drugs, there are currently no government-funded inpatient or residential programs. If you want one you’ll have to search around yourself for a handful of community-led residential ABP’s. The ones that I know are always begging and scraping to find enough money to keep the lights on. (If you want to donate, for just one example check out Talbot House in my home of Cape Breton.) There are some excellent and highly-regarded residential programs like Homewood, which you can access if you - or someone you know - has 10 or 20 large burning a hole in your pocket.

The spectre of withdrawal

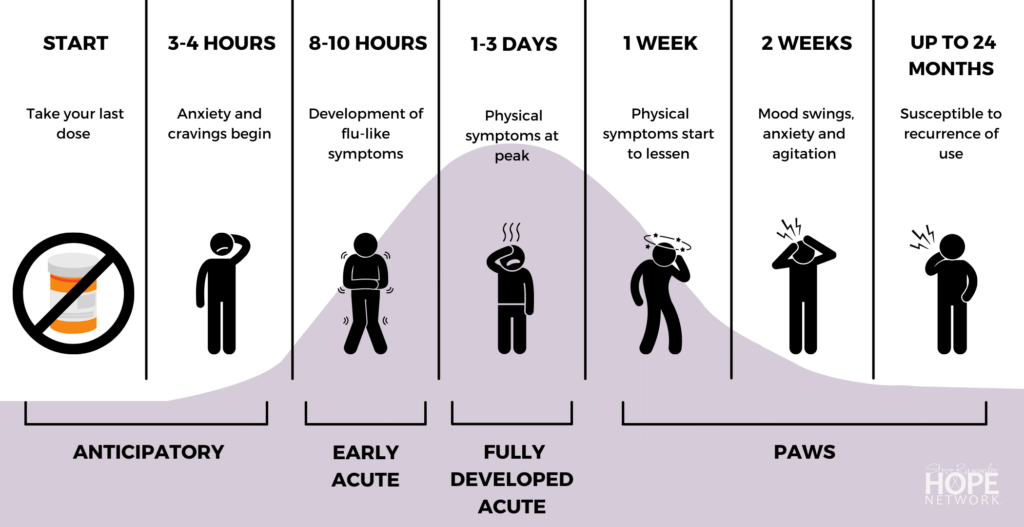

This may seem like an aside, but I believe the exaggeration of the difficulty and danger of opiate withdrawal contributes to the move away from abstinence and is part of the push to go “all in” on harm reduction.

I highly recommend the book “Romancing Opiates” by Theodore Dalrymple (aka Dr. Anthony Daniels). (You can’t go wrong with any of Dr. Daniels’ books, by the way. I think he is perhaps the most brilliant writer of our age.) I’ll give you a Substack-length version of his book here.

Nowadays we talk about withdrawal from opioids as something cruel, inhumane, dangerous, and possibly deadly. We keep people on narcotics or ORP’s for long periods of time (sometimes for life), and if we taper at all we do it extremely slowly. Opiate addicts are given the impression that they can’t stop on their own, and in fact to do so would be dangerous. They get tied into potentially counter-productive ORP’s that are expensive for the taxpayer and coincidentally highly profitable for the physicians who run them, and Big Pharma. Movies like Trainspotting and other pop-culture depictions of opiate withdrawal helped make it the bogeyman it has become.

The problem is this story is wrong. Opiate withdrawal is no doubt very difficult - gooseflesh, chills, sweats, diarrhea, vomiting. I’ve seen it many times and it ain’t no picnic. But PURE opiate withdrawal is not medically dangerous (unlike withdrawal from other substances such as valium or other benzos, barbiturates, or alcohol). People withdrawing from opiates sometimes feel like they WANT to die, but they won’t.

When tens of thousands of heroin-addicted soldiers arrived home from Vietnam at the end of the war, the vast majority simply stopped using. They had things to do, and drug addiction had not been “destigmatized” in their families and communities. When Chairman Mao took over and announced that all opiate addicts would be summarily executed, the vast majority simply stopped using. They preferred to stay alive. When the Beatles/Rolling Stones/every famous musician from the 60’s wanted to kick heroin, they sweated and shat and cursed for a weekend (often in the comfort of the Betty Ford clinic) and then moved on with life.

I still meet many recovered addicts who did the “Cold Turkey” method. One memorable patient had lived in Ontario for years. He got a call that his mom had fallen ill, and he had to come home to Cape Breton tout suite. He bought a plane ticket for Monday. His mom didn’t know he had developed an addiction and he didn’t want her to find out. He needed to be ready to look after her. He paid a friend to lock him up in his basement for the weekend with the instructions to “bring food to the basement window out back but don’t let me out no matter what I say”. He flew home Monday morning a little weak and unwell, but having kicked his opioid habit. When I met him, he hadn’t used in the 12 years since then.

Withdrawal is a speed bump, not a brick wall

My (somewhat belaboured) point is that people CAN and do quit drugs when they really want to. When they are motivated. When they have something meaningful to move on to. Withdrawal is not cruel and unusual. It’s a necessary hurdle that an addicted person must jump over to become drug-free.

Is it better to just rip the band-aid off quickly?

There was a very interesting study done on smoking cessation in Britain several years ago. It compared those who tapered smoking - ie: cut down over time, with the goal of getting to zero smoking - with those who simply quit immediately and dealt with the withdrawal.

The result was surprising to some but fit with my experience with patients. Those who just quit were more successful by a significant margin. Why? Likely because those who slowly taper are actually in a mild withdrawal as long as they are tapering. They are cranky, irritable, and hungry, but are still smoking. They put up with this for many months, instead of the relatively short few weeks of the same (but debatably more intense) withdrawal after just quitting. The chronic withdrawal is so difficult to deal with that many just say “the heck with it” and go back to their original pack-per-day or whatever.

Rip the band-aid off quickly, or peel it slowly and painfully. It seems like the former works better, at least for smoking. I have to wonder - do we make it harder for people to become narcotic abstinent by slow drug tapers? Are we prolonging their agony in a vain attempt to avoid ultimately unavoidable withdrawal and discomfort?

You become who you hang around with

Slow tapers (or no tapers) and ongoing attachment to ORP’s may also unintentionally make it harder for a person wanting to achieve a sober lifestyle to do so. Having spoken with hundreds of patients over the years who have overcome addictions, there is one common refrain: stay away from other users.

If you quit smoking last week, don’t go to a party and hang around with your 3 friends who all smoke. If you quit alcohol, don’t head to a party with your friends who like to drink. If you want to stay off drugs, don’t hang around other people who are using.

Help centres and shelter projects - like those planned for cities like Halifax, Sydney, and Moncton here in the Maritimes of Canada - by nature warehouse addicts. Interestingly, surveys have shown that addicts themselves do not want this either, as they recognize that finding a supportive environment away from other drug users is best for them personally. Integration into non-drug-using environments, not enforced cohabitation and constant contact with other drug users, is what a person needs to be sober and regain a meaningful and healthy life.

Do harm reduction programs really help? Or do they enable users to continue their habit, thus increasing risks overall? Stay tuned for part 3 of “Is there Harm in Harm Reduction”.