The watering down of language

When I was a medical resident in Kingston Ontario in the late 90’s, we would sometimes receive patients from the Rideau Regional Centre. This was a residential facility or “Institution” between Kingston and Ottawa that at its peak in the mid-50’s housed over 2500 mentally handicapped people.

Back then in the 90’s, the government was in the last stages of phasing out these larger centres in favour of “small options homes” and “community care” for the handicapped. Whether this is an improvement is a debate I won’t step into here, except to say “it’s complicated”.

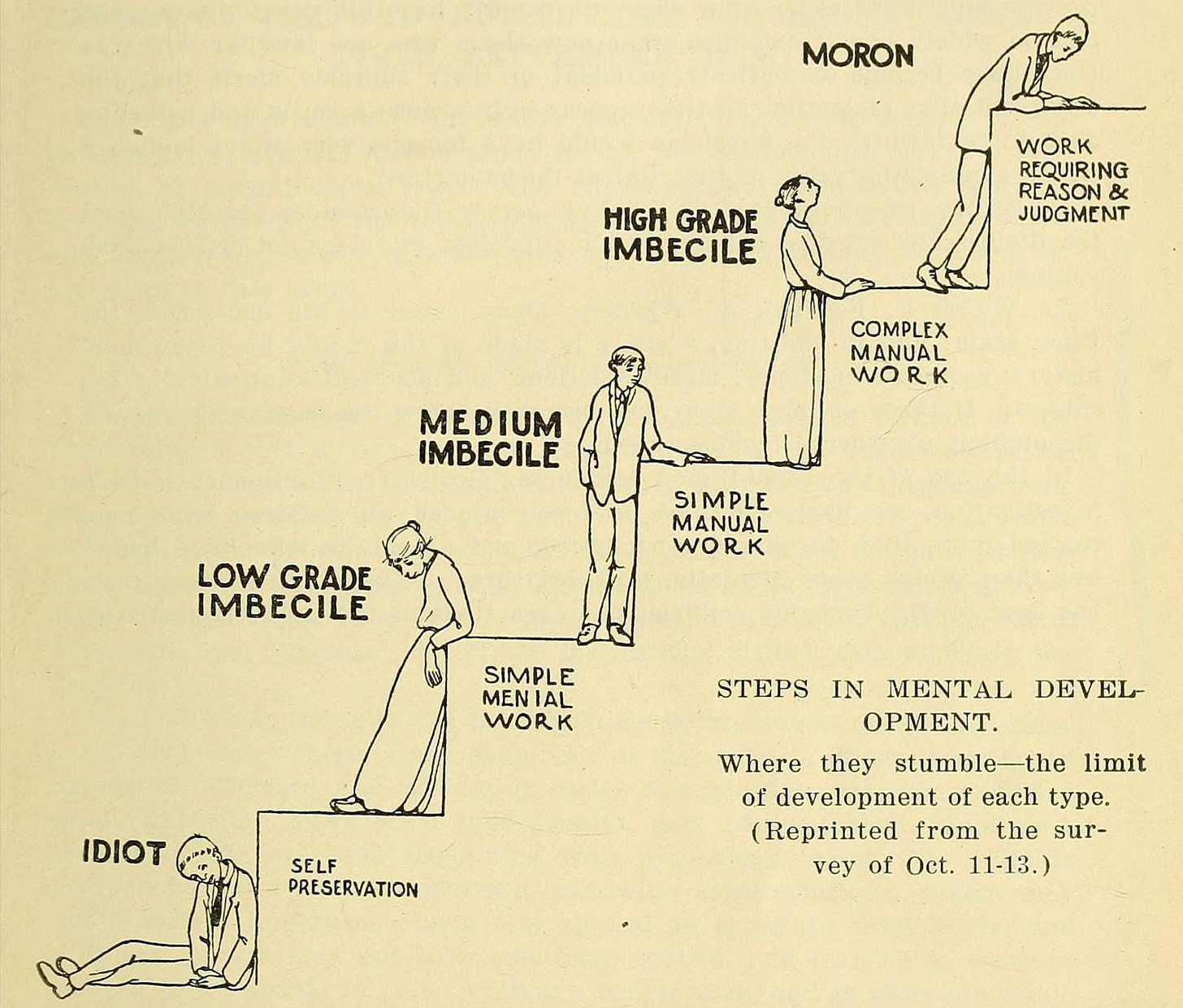

Some of these residents had been admitted to the centre when they were very young, and many were old by the time I cared for them. They would arrive with their original paper charts, some of which had admission data from the 1940’s, 50’s or 60’s. Admission notes included diagnoses such as “Low-Grade Idiot”, or “High-Grade Imbecile”. Back then, these were technical terms. “Idiot” meant someone with an IQ of 0-25, an “Imbecile” between 25 and 50, and a “moron” between 50 and 70.

As I don’t have to point out to you, these terms were co-opted from being technical and medical to being terms of insult and derision. Their use in medicine was abandoned. Numerous iterations have followed. “Retarded”, which etymologically means “slow” followed, but also became a term of derision. So then we used the word “slow”. “Mentally handicapped” followed. “Delayed” or “developmentally-delayed”. “Differently-abled”. Or now I have heard the term “Multiple Learning Disabilities” to describe someone who in 1950 would have been a “High-Grade Moron”.

The peak of “euphemizing” about mental handicaps hit a few decades ago. I remember listening to the news and hearing about the “Association for Community Living”. What was this new organization? Did they help seniors remain in their homes? Or provide affordable housing? A church organization? Were they a swinger’s group? No, this was the new name for the Association for the Mentally Retarded (it is VERY hard to find traces on the internet, as record of its existence now seems to be memory holed). The Association for Community Living supports mentally handicapped people, but there is no longer any trace of that apparent in their name. It has been euphemized to the point of being completely devoid of meaning.

This process has been called the “euphemism treadmill”.

Euphemizing can lead to normalizing

We have followed a similar process with the word “addict”. Many euphemisms have been used. “Drug abuser”, “substance abuser”, “person living with addiction” (as Lionel Shriver says, a description which makes it sound like they took in a roommate), a “person who abuses substances”. We seem to have somewhat settled on “a person with an SUD” (substance use disorder).

Recently the term “a person who uses substances” has come into common usage. The problem with that is that we all “use substances”. I drink coffee most mornings. I bet many of you have taken Advil for a headache. Some might have a drink of wine on Saturday evenings. Cheerios are a “substance”.

The term “a person who uses substances” does not differentiate the average person from someone who has emptied his wife’s bank account to supply his drug habit, wrecked his marriage, impoverished his family, and is living under a bridge. (Could living under a bridge be called “Community Living”?)

It’s not what you say, it’s what you do that matters

Our society tends to develop euphemisms for issues which are uncomfortable or difficult to discuss. But it seems to me that the term you use to describe someone is not nearly as important as the respect and compassion that you actually show that person.

I’ll never forget when one of those handicapped patients from the Rideau Regional centre died, watching 2 of his caregivers completely overcome with tears. The fact that his record indicated that he was officially a “moron” hadn’t stopped them from loving and caring for him over several decades. They wept for him as if he were a brother. On the other hand (if you’ll recall back in part 2), Bonnie Henry is very careful to use the term “people who use substances” instead of “addicts”. But then she says they have a “brain disease” and that they can never get better. Is that respectful? Is it compassionate? We can run on the euphemism treadmill but go nowhere.

When we water down a word, we lose something. There is still some stigma about being an “addict”. It is normal to be a “person who uses substances”. Perhaps this is why I meet lots of people who self-describe as “addicts” or “alcoholics”, many of whom haven’t used or touch a drop in decades, whereas I’ve yet to have met someone who describes himself, or is described by his family, as “a person who uses substances” who has kicked his addiction.

The first step to a cure is a proper diagnosis

We need straight talk. Many media reports muddy the issue of addiction and homelessness, referring to them as “intertwined”. It is suggested - or sometimes said directly - that some people become addicted because they are homeless. Yet in all my years in medicine I have never once met someone with this story. In 2024 nearly every homeless person in Canada is addicted, which suggests the arrow points in one direction, from addiction to homelessness, but not in the other.

If your brother, cousin, or friend called you some frigid winter evening and said that he was down on his luck and needed a place to stay for a while, how many people would tell him to go fly a kite? Not many. I sure wouldn’t. Now picture if you knew that person was addicted, injecting drugs regularly, stealing to support his habit, and had stolen or got in fights at the last few places where he stayed? Would that change your answer? Non-addicts rarely end up homeless, or if they do it’s not for long.

Getting stigma right, not getting rid of it

Julie and I sometimes joke that we need to start a “Restigmatization” movement to counterbalance the destigmatization movement. Why?

Shame is normal and necessary. There are whole books written on this subject. Shaming those who engage in personally and/or societally destructive behaviour is not only reasonable, it’s necessary. Shame helps hold societies together. We could probably steal our neighbour’s bicycle and sell it for money and get away with it, but that would be shameful. We could knock down a little old lady and take her purse, but that would be shameful. The vast majority of us don’t do these things, not because the police are watching us every minute (at least not yet), but because we would bring shame on ourselves and our families. We know certain actions are wrong - there is stigma attached to them. The only way to never feel shame is to not have a conscience.

As we destigmatize drug use, we can unintentional cross a line into normalizing and condoning it. We need to remember that it SHOULD be shameful to be an addict. It is bad for your family, for your community, and for you personally. If there is no stigma, there is less impetus to change.

What is the right amount of stigma? If there is too much stigma and shame, a person can feel beyond redemption, and give up on himself. An addict should not be made out to be hopeless or evil. But they are not just fine like they are.

It’s important to stigmatize the BEHAVIOUR and not the PERSON. An addict is not worthless or irredeemable or forever lost, despite what Bonnie Henry says. But the behaviour is destructive, costly, and socially irresponsible. Hate the sin, love the sinner.

We need to get stigma right, not eliminate it. You can love someone who drank and drove, or love someone who is doing time for grand larceny. But the DUI or their felony is not what you love about them. It’s not what you’re proud of them for. It’s the part that you hope they will change. So it’s not what you put on a t-shirt.

Compassion versus empathy - when does empathy become toxic?

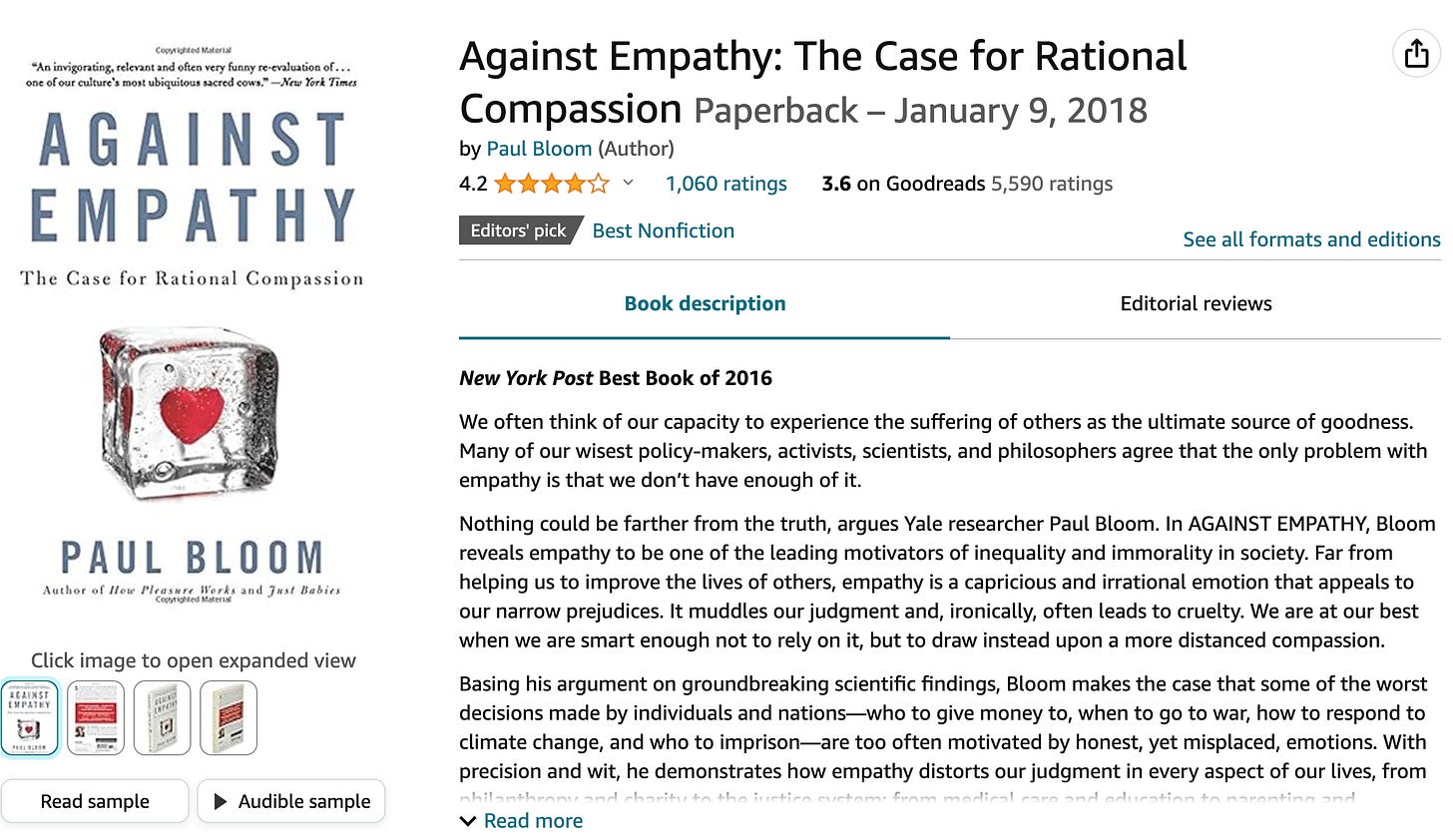

Whole books have been written about “toxic empathy”. “Against Empathy” by Paul Bloom should be required reading for all parents, healthcare professionals, and teachers in my opinion. Toxic empathy is the kindness of heart that makes us want to give every kid a trophy. To let the screaming toddler eat the chocolate bar an hour before supper. To shut down free speech because someone’s feelings might be hurt. To avoid enforcing educational standards because someone might actually fail and feel bad.

Toxic empathy is destructive in many realms, including with drug use. We need to draw lines. We need to say that some things are not acceptable. We need to avoid allowing our natural empathetic instincts to push us over the line from helping to enabling.

American historian and thinker Christopher Lasch said:

“…the ideology of compassion, however agreeable to our ears, is one of the principle influences in its own right, on the subversion of civic life, which depends not so much on compassion as on mutual respect. A misplaced compassion degrades both the victims, who are reduced to objects of pity, and their would-be benefactors, who find it easier to pity their fellow citizens than to hold them up to impersonal standards, attainment of which would entitle them to respect.”

Is the key to success lowering standards?

A number of years ago there was much hand-wringing around physical activity (PA) guidelines. There was debate over what the minimum standards should be. There had been a sharp dropoff in PA over the preceding years, and rising obesity rates. The “solution”? Lower the standards. Experts™ said that having a high standard would mean too many people would fail to meet it, and thus would feel bad about themselves. We needed more “realistic” goals. So your tubby kid could now feel happy if he was active for an hour a day, rather than the previously recommended 90 minutes.

The joke “if at first you don’t succeed, lower your standards” feels like it has actually been applied to drug addiction through changes in language and the move from abstinence promotion to harm reduction.

The healthy solution when someone we care about is not meeting a standard is not to lower it, but to help that person achieve it. The way we talk about and treat addicts in 2024 is a great demonstration of “the soft bigotry of low expectations”.

It seems that in general in modern society, and specifically around the issue of addiction, we have a hard time remembering there is a difference between BLAME and RESPONSIBILITY. But clearly defining this difference is crucial if we want to help those addicted to drugs, but not enable them.

Addiction as a disease

Is addiction a “disease”? To be generous, perhaps in some senses. There are genetic and lifestyle risk factors. There are measurable differences in someone’s brain chemistry over time. We can treat certain symptoms with drugs. Addiction, like many diseases, causes morbidity and mortality.

But with just a bit of thought we see the problem with this model. Breast cancer is certainly what I would call a disease. Yes, a woman’s choices - smoking, obesity, poor diet, and lack of exercise all increase risk, as does genetic susceptibility, but breast cancer itself is not A CHOICE.

In all my years as a doctor, I have never seen a woman cure herself of breast cancer by waking up in the morning, looking in the mirror, and saying to herself “that’s it, I’m sick and tired of breast cancer and I’m just not going to have it anymore”. That just doesn’t happen. But I know MANY recovered addicts who have cured themselves of their addiction in exactly that way. They are in my family, they are my friends, they are my co-workers, I play hockey with them. They are people I admire. If addiction is a “lifelong disease” then why are there so many more ex-addicts than current addicts?

Speaking about addiction as a disease is infantilizing and disempowering. It suggests to an addict that he is a victim. That he is helpless. That he has no choice but to go on suffering.

Addiction is a BEHAVIOUR, not a disease. It’s a behaviour that is hard to change (by definition), but one that is possible to change. People can, and do, change their lives. They can and do wake up one morning and say “I’m done with this. Enough.”

The Experts™ look down on the addicted

Does the view that addicts are helpless victims - a view that is at the base of our harm reduction strategies - rob addicted people of their own human agency?

We have essentially given up on abstinence. Which in my mind is the same as giving up on addicts. Most recovered addicts I have met talk about having hit “rock bottom” before quitting their habit. By cushioning their “rock bottom” with harm reduction, it seems to me we are in all likelihood preventing abstinence. We are trying to fill the god-shaped hole in addicts hearts with clean needles and now with free supply of government-provided drugs.

In Brave New World, Aldous Huxley suggests that a drugged populace does not question authority, but rather depends on it. From Valium to Prozac to Ritalin and Adderal, and now an implicit acceptance of opioid addiction as a life choice. Are we creating a dystopia?

Stay tuned for Part 4 of Is there Harm in Harm Reduction: Data, Dystopias, and Detrimental Effects