We bring you an interesting take once again from Anonymed.

Some of you will recall that a couple of months back I wrote about Ozempic and was skeptical. Is there such a thing as a wonder-drug for obesity with no side effects? Seems a little too good to be true. Not a bandwagon I’ll be jumping on yet.

During the pandemic, less than 3% of deaths were from COVID, and the vast majority of those 3% were in elderly or very elderly people with “comorbidities”. One of the most common sets of comorbidities was obesity-related disorders: type 2 diabetes, vascular disease, atrial fib, etc. And out of the other 97% of deaths, many were obesity-related as well. In short, even in the times of COVID, obesity killed far more people than did COVID. So why didn’t his royal majesty Justin Trudea villainize the obese?

Below are some interesting musings from Anonymed on this issue.

Externality: The indirect effect of one agent's consumption activity or production activity on the well-being or economic activities of other agents - Oxford English Dictionary

Canada is one of the only countries in the world with a single-payer healthcare system. The public “option” is, at least theoretically, the only option. Despite mission creep from the private sector, we are - and, perhaps more importantly, view ourselves as - the world’s example of what “socialized” medicine can be. It is part of our history and, historically at least, a source of immense pride.

For a long time, the question has been: at what point does this pride occasion a fall? In the most recent Commonwealth Fund analysis (2021), which grades nation-states on the effectiveness of healthcare delivery, Canada’s Medicare system ranked tenth overall out of eleven high-income countries. In 2017, it was ninth. Even in matters of “equity”, our socialized system ranks near the bottom. We could fill two books weighing the pros and cons of different healthcare organizational structures, but one thing is plain: the Canadian system is struggling.

Unfortunately, our difficulties were never more apparent than with COVID policy. Socialized medicine comes with the same liabilities as socialist systems in general - namely the propensity to subordinate the individual to the “wellbeing” of the collective - and, for all the sanctimony about its “equitable” nature, it didn’t take long for government-procured medicine to mete out decidedly unequal treatment when faced with a crisis. Prioritizing minority populations for COVID treatments seemed almost reasonable compared to calls (from elected officials no less!) to deny health care, as well as basic freedom of movement, to the unvaccinated (NB these draconian proposals continued apace even once Omicron was shown to be significantly less hospital-stressing).

Like most places, Canada was overwhelmed by COVID. This is understandable, but the consequences of single-tier healthcare were far-reaching. Nearly all developed countries, to their shame, deferred to pro-lockdown, pro-mandate bureaucrats. Where short-sighted pandemic policy is concerned, Canada was in good company. But our public system also created the conditions by which draconian measures could be justified by reference to the sanctity and fragility of that same system.

There are complexities therein, but when a citizen pays for their own healthcare through a private insurance company (like a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO)) it is harder to make the argument that the system “gets a cold” whenever any individual happens to sneeze. While it is true that carelessness with one's own health may ultimately impact the premiums (and thus access) of others, it primarily affects one's own bottom line. When healthcare is collectively funded, as it is (at least theoretically) in Canada, however, individual rights naturally have less purchase, and authoritarian measures are therefore easier to rationalize under the guise of curbing “externalities”.

The problem is, in a public system like Canada’s, everything is a potential externality. Every adverse health outcome (or behaviour that might lead there) that could theoretically be avoided costs the system eventually, and thus impacts the health of the larger community. Technically speaking, this is true of any taxpayer-funded endeavour, but the argument gains special potency in a life and death arena like healthcare. The consequences of any outsized pressure on the system can be dire, and with these higher stakes comes heightened scrutiny of anything thought to affect this delicate balance.

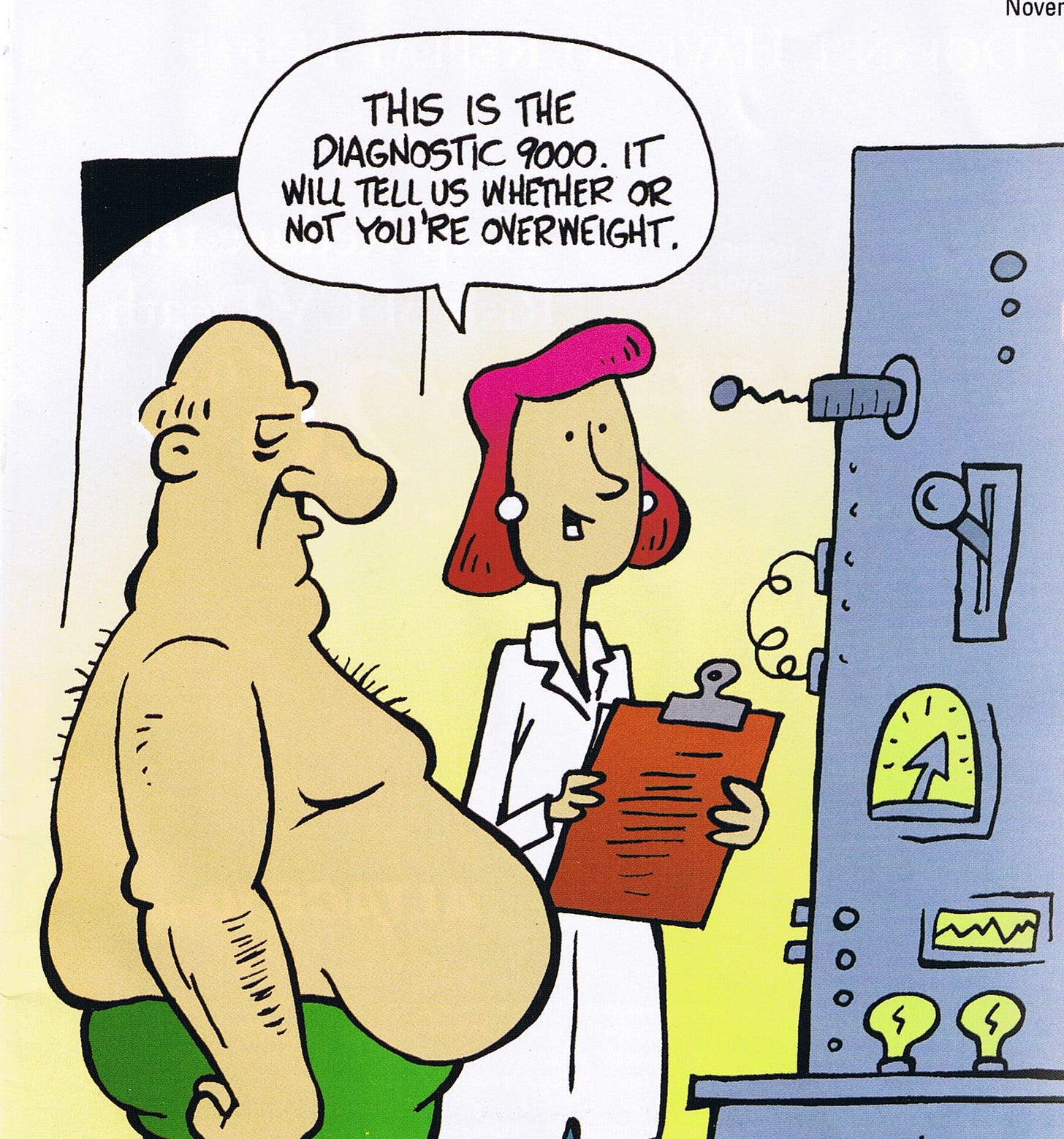

Which brings us to Ozempic (semaglutide), the diabetes treatment cum weight-loss wonder drug receiving so much attention of late. Reports vary, but Ozempic is known to deliver such rapid and predictable weight loss that celebrities (and many doctors) have been using it for this purpose for years (it recently received approval for weight loss under the name Wigovy). In several large randomized control trials (RCTs), the drug resulted in a mean decrease in weight of 5% at three months and 12.4% at 6 months. These are incredible findings. With those kinds of results, Ozempic has the potential to rescue a generation from premature morbidity and mortality. What I want to know is, if the drug is that good, and the condition of the health system that dire, where are the mandates?

Obesity is a public health crisis of its own. Its negative effects are such that aggressive treatment up to and including surgery for obese children is now being advocated at the highest levels. Despite our wariness of fostering undue stigma, everyone in medicine knows that the individual and societal costs of obesity are astronomical. According to Obesity Canada, direct costs of the disease, which afflicts about a third of Canadians, amount to about 5 billion dollars per annum (total health expenditures are in the range of 220 billion). Again, this is just the direct healthcare component, which does not include “productivity loss and reductions in tax revenue.” And remember, this was pre pandemic, before we compensated for a dearth of freedom with an excess of freedom fries.

Costs like that would be worrisome for any system, but for a socialized system, they’re kryptonite. Other than smoking, which most sources estimate costs the system about 6.5 billion annually, what straw is more capable of breaking healthcare’s back than obesity? If every health decision truly impacts the health of the collective (as the COVID czars repeatedly claimed) and someone’s not doing “the right thing”, then should they not be obligated to do so? I’ll bet a plug nickel that if a truly effective anti-smoking drug came along, the obligatory option would at least be floated. So why not in this case?

I know many will roll their eyes at the comparison between a virus-mediated global pandemic and a chronic disease like obesity, but I’m not so sure it’s that big of a stretch. Obesity has far greater knock-on effects than COVID (even taking the long-COVID crowd at their word). In addition to diabetes, heart disease, strokes, high blood pressure, respiratory problems, joint degeneration, and fatty liver disease (which is becoming an epidemic of its own), obesity is increasingly implicated in a variety of cancers, mental health conditions, and autoimmune disorders, suggesting current costs will only grow.

Fine. But even those who accept the validity of the comparison in terms of healthcare costs and long term effects could counter that obesity is different from something like COVID because there is a fix for COVID - a one time (ok fine, five-time?) jab and it’s done. Obesity, on the other hand, is complex, chronic, behavioural, and much less amenable to intervention.

For that point to hold, two things would need to be true. First, the COVID vaccine (or other therapy) would have to provide more than run-of-the-mill symptom management. It would have to “cure” the disease (that is, stop you from getting it). For a time, this was thought to be the case. When the vaccine was first studied, there was reason to believe it might actually stop infection transmission. This turned out not to be true, at least for subsequent variants. And so we were left with a vaccine that would reduce illness severity and prevent hospitalization (which is still pretty good) but do little to eliminate the problem. In the long run I think that mandating medical treatments on a societal scale is ethically dubious and impractical no matter the stakes. But if you had a vaccine which reliably stopped transmission of an unprecedentedly lethal virus (and thus made eradicating the virus entirely possible) then at least the case could be made that the public interest should prevail. But once the dream of zero COVID was dead (which in reality might have been sometime early in 2020), the argument for mandating the vaccine, as much as there ever was one, died. Any short-term protection of the healthcare system was just kicking the can down the road.

Many held on to the notion that requiring vaccines as a prerequisite for getting Starbucks in the morning was still warranted because reducing illness severity remained essential to prevent our health systems from being overwhelmed. While we were initially told mandates were needed to protect the vaccinated from the unvaccinated, once we realized transmission wasn’t altered all that much by the vaccines, it then became necessary to protect the unvaccinated from the vaccinated and the other unvaccinated in order to, again, protect the system. Which brings us back to the idea of externalities. COVID may have been a particularly significant externality, but it was an externality nonetheless. And with vaccines merely reducing the severity of the disease, it became more like a chronic disease. As Chris Rock once said of AIDS, they found a way for us to “live with that sh*t.”

The second condition needed to obviate the comparison would be for obesity to truly be incurable, chronic and resistant to effective intervention. While bariatric surgery and other weight loss drugs have been around for a long time, I’m willing to concede that traditionally there has been no quick fix. But that has changed, has it not? Drugs like Ozempic have changed the game. If a weekly injection can reduce the risk of umpteen diseases and their associated costs, this is, for all intents and purposes, a “vaccine” against those illnesses. And if the ultimate argument for mandating COVID vaccines was to protect the system, how is this any different?

There are interesting parallels regarding the downsides of intervention as well. Like the COVID vaccine, Ozempic is to some extent novel. When we told people they had to get vaccinated but weren’t allowed to get too ruffled about the potential side effects, we were in effect saying that the long term chances of this vaccine causing you to grow a third arm were sufficiently minuscule compared to the known benefits of the vaccines. The argument would be the same with Ozempic. Sure there is nausea. Sure there has been data suggesting an element of oncogenesis (particularly in the thyroid). But compared to the benefits of conquering obesity, this is nothing. Should we therefore consider denying intensive care services to Ozempic-deniers if they’re dying of an obesity related disease? What about imposing a health tax? What about restricting access to restaurants? Luckily obesity isn’t contagious (at least not in the traditional sense) but would restaurants not be a target rich environment for the propagation of the disease? According to COVID logic, we should only have so much tolerance for those wary of saving so many of their fellow citizens, and for those insufficiently committed to protecting our sacred system from oblivion.

Obesity is a curse. While it is true that some people are genetically predisposed to catch it, as well as suffer mightily from it when they do, it is no different than any other disease. Such people certainly deserve compassion. But the fact remains that there are few ailments in the western world whose effects we would be better to mitigate. And when the consequences are such that the whole population suffers (particularly those “equity deserving groups”), public health officials, we are told, must act. If they’re not going to do so here, they need to explain why some externalities matter and others do not. Would they argue that it is inhumane to force medication on people? Or that those who resist would face undue stigma? Perhaps coercing people might turn them and others against the whole system? Maybe even undermine trust in public health for a generation? I agree we wouldn’t want that.

Thanks for sharing... parallels are not always obvious, and attention needs to be drawn. Thanks for your service, and shining much light!

Obesity isn't a disease. Diseases can stem from being overweight - that I can fully agree with. There are many reasons people become overweight. For those that are, those reasons need to be uncovered and hopefully resolved. So many people want a quick fix to their problems, such as taking a drug to lose weight. But will they get in touch with how those extra pounds accumulated in the first place? I'm going to take a quick assumption and say no.