Ozempic - wonder drug or false hope?

We should take all Big Pharma claims with a shaker of salt

If you haven’t heard of Ozempic yet, my guess is that you live in a cave (strange choice, but OK) or have quite sensibly stopped following mainstream media (in which case - high five! - it likely means you’re better informed than your MSM-imbibing peers).

The generic name of Ozempic is “semaglutide”. Semaglutide is also is sold under 2 other brand names: Wegovy and Rybelsus. Three names for the same drug (ever wonder why it’s hard to keep track?). Semaglutide was developed specifically for diabetes and sold under the name Ozempic, whereas Wegovy is a new name and dose of the same drug marketed specifically for weight loss. Rybelsus is the pill version, whereas Ozempic and Wegovy are injected.

How does it work

In brief, semaglutide is a “GLP-1 agonist”. Glucagon-like peptide is a hormone that is produced by your gut when it senses that it is full and you don’t need more food. This hormone sends a signal to the brain that you aren’t hungry. Think of that feeling you get when you’ve already eaten seconds at thanksgiving and someone offers you thirds. Uh, no thanks!

GLP-1 also stimulates the pancreas to produce insulin. Insulin is needed to help the body move sugars absorbed from digestion out of the bloodstream and into storage in the liver and muscles as glycogen, and into fat cells as well.

This combination of decreasing food intake and helping move sugar out of the bloodstream is why this drug is useful in reducing blood glucose levels in Type 2 diabetics, who are almost universally overweight and overfed. And it’s easy to see how, as a side effect, it produces weight loss through reducing our sensation of hunger and thereby the number of calories we imbibe.

Ozempic is not the first GLP-1 agonist (the first was exanatide, approved for use in the USA in 2005). But it is the most successful and, I’ll wager, the first whose name you recognize. Its maker, Novo Nordisk, figured out that it has a blockbuster drug on its hands. Once the weight loss side effect was noticed, it didn’t take long for it to be marketed aggressively, as the company pivoted from marketing to diabetics, to marketing to that big chunk of the population who would like to lose weight.

Wouldn’t it be great to increase our potential market by 10X?…

Keep in mind that the percentage of the population with diabetes ain’t small (about 6% are known diabetic, and perhaps 3% have diabetes but don’t know it yet). So that’s a pretty large and lucrative market to begin with. But if the market expands to include all overweight and obese people, that’s two-thirds of the population. Banzai!!! And this is not to mention the significant number of patients in the normal weight range who want to be thinner - to look better in a bikini, in a dress, at the gym, or to be slimmer to achieve athletic goals.

The next step for Big Pharma after marketing a drug directly to patients is to “educate” doctors, nurse practitioners, and other prescribers. That way they are primed and ready to pull out the prescription pad once that newly created army of patients who “need” the drug come knocking. Rules on direct marketing and promotion to physicians were tightened in Canada 20 years ago. A drug rep used to be allowed to take me golfing and buy me supper. Now they can’t give me a pen. But drug marketing is like a hydraulic fluid, and sealing up one hole just forces it out another outlet. Drug companies have learned to do an end-run around these rules by creating “educational opportunities” for doctors, like this one that recently landed in my inbox. Note the sponsor…

The Quest for the Perfect Weight Loss Drug

The quest for the perfect weight loss drug is not new, although it’s far more frantic now, given how many of us are fat. (And as mentioned above, how many who are healthy weight but would like to be skinnier.)

The first fat-busting pills were advertised in the 1880’s, and amphetamines (Fenfluramine) were being approved and marketed for weight loss as late as the 1990’s. (Oops - fen-phen turned out to cause heart problems, and approval was rescinded after numerous deaths).

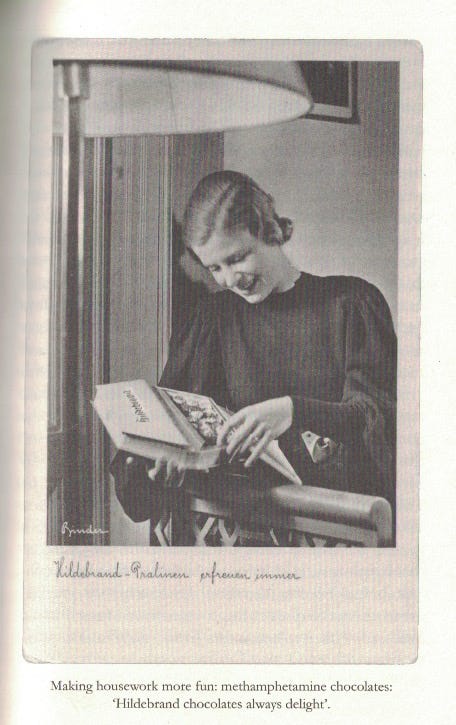

I recently read a book about the use of drugs in nazi Germany (punnily called “Blitzed”) which, among other things, detailed how the new wonder drug methamphetamine was developed by then-new Big Pharma. It was sold as a miracle pick-me-up not only to soldiers, but to down-in-the-dumps housewives as well, with the beneficial side effect of helping to melt away those extra pounds.

Even during my few decades in medicine, several weight-loss drugs have come and gone. The above mentioned fenfluramine was just one example. Orlistat - a drug that prevented your GI system from absorbing fat, looked promising and made it to market. Sadly (but predictably IMO), it was intolerable for patients. Fat is normally absorbed into your bloodstream in the small intestine and so does not normally make it through to your colon in large quantities. The colon is not designed to deal with a bunch of fat entering it. Thus, patients on Orlistat became flatulent and had intolerable diarrhea and “anal leakage” (somehow a very sanitized term for something quite unsanitary). Similarly, Olestra was a synthetic fat that made things taste great. But since it couldn’t be absorbed in our intestine it didn’t count as calories. It went out of fashion due to the same side effect profile. And contrary to what one might predict, there was some indication that it might paradoxically cause weight GAIN.

Various other stimulants that reduce appetite have come and gone. Some “unofficial” stimulants are still used (in part) for controlling weight, like nicotine, cocaine, and meth. One of the reasons some people start (or stay on) these drugs is that they promote and maintain weight loss.

All that to say that miracle weight loss drugs aren’t new. They are a holy grail for drug companies. There has never been one that was “safe and effective”, even though every new drug starts out that way.

So back to Ozempic

Ozempic (semaglutide) is quite new, just a few years in wide use. Big Pharma’s (in this case a smallish company called Novo Nordisk, mentioned above) advertising is clearly working. In fact, its sudden popularity for weight loss has caused such a market demand that there are major shortages.

I’m getting more and more requests from non-diabetic patients to “get approved” for it. They want a prescription, and ideally they hope that they can get it “free” - ie: paid for through taxpayer funding - if I can fill out the right forms. (Cost is somewhere from two to three hundred dollars per month in Canada).

For anyone interested, Bari Weiss covered the issue of Ozempic very well on a podcast that is worth the time. The podcast features a (sometimes fractious) debate between 3 experts with differing views on the issue, including the difficult and politically incorrect topic of personal responsibility and weight loss. (Why does our society always think answers to difficult problems are to be found at the bottom of an empty pill bottle?)

We should know by now…

Yeah, and this includes Ozempic. We already know a few of the side effects, but others will only become apparent as we have more information to see in the rear-view mirror of medicine, or “retrospectroscope”.

There are by definition no long-term outcome studies on Ozempic, since this is a new drug. Does this sound familiar in the post-COVID era? I wonder if I’ll be in trouble for creating “Ozempic hesitancy”.

This drug is being marketed as a long-term/lifetime drug. It’s not something you go on for a few months, lose weight, and then go off. We have no idea what the side effects will be for someone who has been on it for 5, 10, 20 years or more. Despite this, new American Paediatric Association guidelines on weight loss suggest early intervention with weight loss drugs and bariatric surgery. And the FDA (ever trustworthy, and no pharma bias I’m sure!) has approved semaglutide for children as young as 12 years old.

How does this drug affect puberty and development? What are the potential dangers for a 40-year-old who has been on Ozempic since age 14? We have no idea.

Will there be a “rebound effect” for people who eventually stop this drug? ie: like many diets or diet drugs, will people’s weight problems be worse if they try to stop than before they started it in the first place? Time will tell, but there is some indication already that this may be a problem.

It’s all fun and games until someone hurts their pancreas, thyroid, or brain…

Pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas. This can range anywhere from mild (maybe that bellyache and nausea you had 5 years ago was a mild case from eating something that didn’t agree with you) to deadly. And about 1 in 1000 people per year who take Ozempic get it (if you trust the FDA’s numbers). How does this risk balance against potential long-term benefits? We don’t know, since there are no long-term studies yet.

Use of Ozempic seems to cause an elevated risk of thyroid cancer, at least in animals. The prevailing Big-Pharma-Influenced attitude seems to be “Well, but we don’t know if it will in humans, so go ahead and take it”. This is the exact opposite of the precautionary principle. Human risk for thyroid cancer from semaglutide is not yet studied, particularly in the long term. How big is the risk? Does it increase the longer one is on the drug? Time will tell.

Does Ozempic have potentially negative psychiatric side effects? It’s weird to think a drug that is designed to work on your bowel could do that. But 95% of serotonin - a very important neurotransmitter - is produced in the gut. And GLP-1 agonists decrease that production. (listen to the above-linked Bari Weiss podcast for a good discussion of this issue).

How important is serotonin? SSRI’s (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) are by far the most common type of antidepressant prescribed in the world, and are designed to INCREASE the amount of serotonin in the brain. What does reducing that production in the gut do to our mood? To our personality? Will this end up having permanent brain effects even if the drug is stopped? Who knows.

My guess is that any negative effects that decreased serotonin has on mood in the short term are balanced by the positive psychological effects that weight loss engenders. Only long-term studies will show the psychiatric effect of Ozempic over years. Will this be an issue? Who knows. But there is reason for concern and vigilance.

The final concern about semaglutide is - to quote Donald Rumsfeld - the Unknown Unknowns. What other side effects are going to show up that we as yet have no clue about? It’s safe to wager that the answer is not “none”.

Be not the first

One of my favourite teachers at Dalhousie medical school had been a small-town GP for a number of years before going back to train as a specialist, and eventually to teach at Dal for many years. He was very wise, and said a number of things that have stuck with me over the years. It was from him I first hear this saying in relation to medical treatments:

Tailoring Treatment

Modern medicine has created innovative, amazing, intensely powerful and potentially dangerous treatments. Taking these treatments makes a lot of sense for someone who has a serious disease. But for someone who is not “sick”, the risk-benefit equation often doesn’t add up in favour of using the drug.

If a well patient wants to take extra vitamin D or vitamin C, I tell them “go for it”. There’s really no downside. If they ask about taking ibuprofen (a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, or NSAID) for their sore hip, it gets more complicated. Do they have high blood pressure or kidney problems? If so, NSAIDs might do more harm than good: putting up with a sore hip sure beats kidney failure. Chemo can save lives, but has terrible side effects including death in rare cases, so should be deployed VERY carefully and only to the right subset of cancer patients.

Where does Ozempic fall on this spectrum? Without long-term data on benefits and risks, the answer so far is: “Who Knows?” Perhaps there is indeed a subset of patients for whom it makes sense; for whom it may decrease diabetic complications or even extend length of life. Out-of-control diabetes can, after all, permanently damage organs. Sadly, many type 2 diabetics will not make the lifestyle changes necessary to fix that problem. Is Ozempic a reasonable choice for them? Perhaps. But starting a 68-year-old diabetic with neuropathy and early kidney damage on Ozempic is a far different discussion than starting a chubby but well 12-year-old.

Fools Rush In

I never prescribed Vioxx - many of you will recall that this was an anti-inflammatory painkiller that was “safer” than older NSAIDs, largely in that it was less irritating to the stomach. It came out early in my medical career. It was marketed HEAVILY, to the point where drug reps made veiled threats suggesting that docs like me who didn’t switch their patients off of old NSAIDs and onto Vioxx might be legally liable when our patients developed ulcers. But I was already skeptical of Big Pharma, took the time to read what research was available myself, and concluded that Vioxx was “too early for prime time”.

When Vioxx was withdrawn from the market, I breathed a sigh of relief that I had not been one of the docs who experimented on my patients. If others are comfortable using their patients as guinea pigs, that is their prerogative. As long as the patient is fully informed and agreeable, so be it.

Like Vioxx, for now I’ll be holding off on starting my patients on Ozempic. I will be not the first to try this new thing (although I have renewed it when other docs have started it and the patient has asked me to continue it, after expressing my concerns). If we have more fulsome and positive data in 2030, I may be persuaded to jump on the bandwagon. If I’m still around, I’ll write an updated Substack then. Mark your calendar.

At this point, anything pushed hard by big pharma should be treated like a deadly poisonous snake until proven otherwise.

Thanks for the info, and particularly thanks for the wisdom of being a Doc who does not use their patients as test subjects -wise!