This is a real change of pace for our Substack, which has always stuck to more weighty matters. Work has been overwhelming me, and I needed some writing R&R. I thought this story was worth posting. I won’t be hurt if you skip it, but perhaps a little lighter fare as we head into the holidays is good for the spirit, amongst a lot of angst, doom and gloom. I hope you enjoy it!

Pets as Patients

Doctors often get asked their opinion on veterinary medicine issues. But we know bupkis. Humans are all built pretty much the same. What’s poisonous to one human is poisonous to the next.

As a family doctor, I see a wide range of things and need to know a bit about everything. My knowledge is “a mile wide and an inch deep”. In a single morning I can get asked a huge range of things. Is this lump on my scalp a cyst or a cancer? I just lost some weight and I’m worried I have cancer. Why do I get a “zinging” feeling in my head when I bend over? My right leg is cramping every time I run. It’s hard to learn about so many organs, so many diseases, so many treatments. But at least I just have to know about one species.

I often wonder how vets do it. What must their day be like? I imagine it’s something like this: “Mr. Billy - my pet orangutan - is having some bowel issues.” “I think Lily - my cat - is depressed.” “Larry - my iguana – is having issues with his scales falling out.” Plus, veterinary medicine patients have sharp teeth, claws, and poisonous fangs. Mr. Billy could and would tear your arms off if you try to do a rectal exam on him.

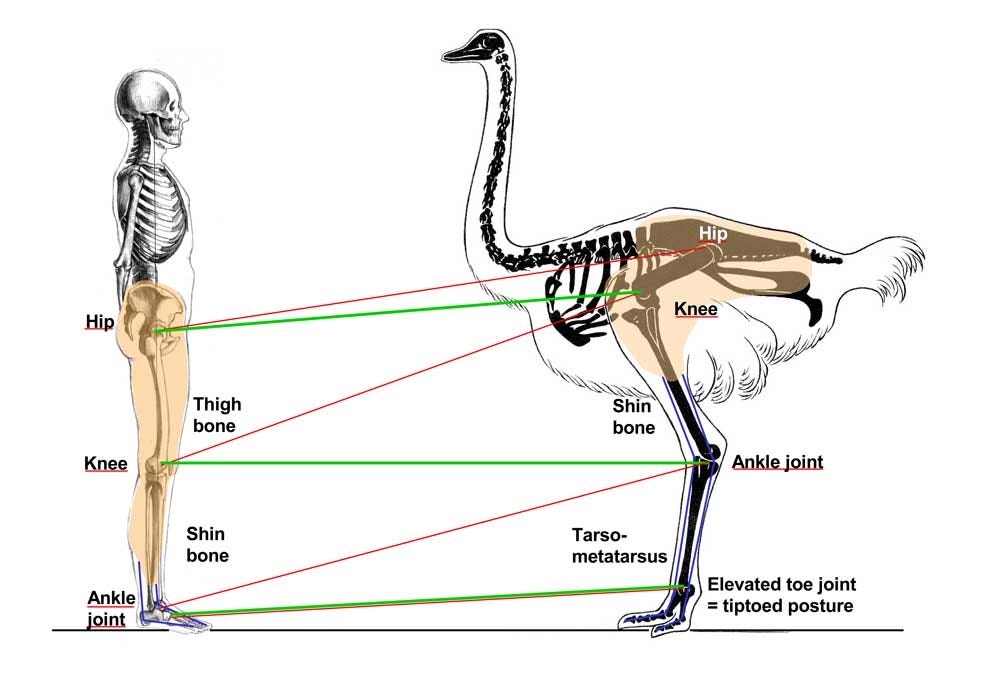

Animals come in all shapes and sizes and variations. Their organs are in different places. They have extra stomachs and eyelids. Beaks. Wings instead of arms. Tails. All kinds of weirdness. And to boot, a drug that is a useful painkiller to one species is a deadly poison to the next. So in general, I approach any request for advice on animals with my 10-foot verbal pole. “I have no idea. I might kill your pet if I answer”.

One of my favourite funny true stories from one of those Reader’s Digest reader submissions was from a physician who worked in a rural area in the prairies of Canada. There was no vet handy so he would often get asked about animals. What do you think about the boil on my cow? My cat is a little lethargic, doc. Etc. He was doing a house call on an elderly lady when the grandson – a little boy – asked if the doctor would look at his hamster. It wasn’t acting normally. The hamster was curled up in the corner of the cage. The doctor opened the top and tentatively poked at the hamster. Which promptly chomped down on his finger. The surprised doc reflexively yanked his hand out of the cage. But the hamster was now attached, and only detached itself at the apogee of the arc of the doc’s hand. The poor little critter flew into the air and across the room towards an attentive and interested German Shepherd, who gratefully opened his mouth, caught and ate the hamster before it hit the floor. (In a way, the hamster was cured of his illness – it was an early version of MAID.)

And that’s a perfect example of why I avoid animal medicine as a rule.

But a couple of times I did stray into that world.

Huddie’s Cyst

When I was still a medical resident (read: “poor”), our lovely dog Hudson (his origin story is an interesting tale for another time…) developed a large cyst. I had a vet friend who had noticed it when patting him and confirmed it was benign. Over time it got big enough that it was a bother when brushing him. And even worse, everyone who patted him (and he was popular!) would say, “did you know your dog has a ...”. I know, I know! A big lump on his shoulder!

The cost of removal at the vet was a few hundred bucks – a LOT of money for us with a mortgage, car payments, student loan payments, and only residents’ wages. I had removed lots of cysts from humans. How hard could it be? My vet friend agreed to spirit me some Acepromazine, an animal sedative. I collected surplus local anesthetic, stitches, etc. from work.

We injected Huddie and within 10 or so minutes he was nicely stoned, wobbly and sleepy. We shaved the area and I started the procedure. Then I started to get wobbly myself. What the hell? I felt sweaty and weak. By this time I had a lot of experience in the ER dealing with all kinds of blood and catastrophe, and had never had that happen before. Hell, I could assess a sucking chest wound while eating my lunch with absolutely no problem! And yet here I was weak and woozy from operating on my dog. I couldn’t exactly stop halfway through though. Julie got a cool cloth and put it on my head. I managed to finish, but afterwards had to lie down for a short time before feeling normal again. The operation was a success, but the surgeon nearly expired.

Best I can figure, my weakness was something to do with seeing a loved one (yeah, Huddie counted as that) bleeding or sick. It happened again when I gave Julie a flu shot. I’ve learned to farm out any medical procedures on family to other docs.

The Ostrich

One Sunday morning shortly after waking up after a late evening Saturday shift I got a call from Norm Kienitz, a fellow ER doc and the head of our department. “You busy today?” Nope, I said, I’m not working until 5PM. “How would you like to operate on an ostrich?” he said.

I told him that given the likelihood that even if I lived several lifetimes I would never be asked that question again, how could I not say yes? “I’ll pick you up in an hour” he said.

A local hobby farm had a number of exotic animals and doubled as a petting zoo and place for field trips for local schools. They had a male-female pair of ostriches. I learned that there are several subspecies of ostriches, and that these, “Big Reds” as I recall, were the biggest. The female was smaller than the male by a good bit, but she (the patient) was upwards of 250 lbs. I’ll call her Ezmerelda, just because I think that’s a great ostrich name.

Ezmerelda had cut herself the evening before. She had stuck her neck through a fence looking for food, and when pulling back through caught her neck on a piece of barbed wire. It cut her from near the base of her neck to her chin.

Now, for you as a human such a cut would be long enough – a few inches. But an ostrich has a lot of neck. So for Ezzy this cut was somewhere above 18 inches long. Thus the reason I got asked to come.

The vet (Darren Lowe – an awesome guy who wrote a very funny and lovely regular column for the local newspaper called “Animal Tales”) had been called, and realized he would need people who could sew acceptably well but very quickly. That is to say, he needed a couple of ER docs. He knew Norm, and asked him if he could get a second doc. Because Darren didn’t know how long the animal could be sedated for, he figured that it would take half the time to close the wound if each doc could start sewing from either end and meet at the middle. Darren would handle the anesthetic while we sewed.

Keep in mind there is no book called “Grey’s Textbook of Ostrich Anesthesia”. There are probably only a few cases ever in the entire world where someone has had to anesthetize an ostrich. And recall as I said earlier, what is a useful drug for one species is poison to another. So what to use? Darren spent time on “the googles”. He got in touch with someone from Australia who had operated once on an ostrich. He made his best guess as to the safest and best drug, and the right dose.

The farmer, a helper, Norm and myself, and Darren got into the pen. Her wound was huge but overall Ezzy looked pretty well. The farmer didn’t think she had lost a lot of blood, and despite the wound being long it looked like it hadn’t cut into her deeper neck.

It is disconcerting being around a bird who outweighs you by 70 or more pounds, especially one that makes very direct and suspicious eye contact with you, and is as tall as you (I’m 6’3”). They had warned us to not come close until it was time, as an ostrich’s kick can be deadly – it can disembowel a man. I made sure to stay in front of her as she shuffled around the pen. A few minutes later, as he was getting the drugs ready, Darren noticed me working to stay in front of her. “Uh. You know they kick forward, right?” he said. I replied that everything I knew about ostriches, I had learned from cartoons. And in cartoons they kick backwards. And also bury their heads in the sand when they are scared. It turns out the former is as false as the latter. Damn cartoons!

The farmer and his helper managed to corral Ezzy, and Darren injected the sedative. It took a long time as I recall, but finally she started to stagger, then was eased onto the hay. Norm and I took the cue and pounced. We irrigated and scrubbed the wound like crazy to get all the dirt out (although surprisingly it wasn’t that bad – I assume because an ostrich neck is nowhere near the dirty ground). We sewed like we had never sewn before as Darren continued to monitor pulse and breathing. We met in the middle of the wound, stood back and looked at our work. It was altogether decent! We were on the road to being qualified ostrich surgeons!

Then Darren looked downhearted. The pulse had been getting weaker. Now he couldn’t feel one. Soon after that, her chest stopped rising and falling. The bird was dead. And nobody knew how to do ostrich CPR or life support. Was the dose wrong? Was the medication poisonous to her? Or had she lost too much blood and was already doomed despite our best efforts.

I have to say it was surprisingly emotional. All of us had worked so hard, and were so keen to save this huge, majestic animal. Now we stood back and looked at her lifeless corpse lying on the hay, the light in her eyes gone out. It was profoundly sad. She was one of God’s beautiful creations.

I don’t know what they did with her. Was her meat fed to the other farm animals? Or to humans? Apparently ostrich meat is very tasty and healthy. But would the sedative be in her flesh and a danger to one who consumed it? I don’t know. Somehow I hope they buried her on the hillside there, looking out over the northwest arm of Sydney Harbour, facing the summer sunsets; a resting spot a world away from her ancestral homeland but fittingly beautiful.

This made me laugh and then I didn't expect the ending; therefore it saddens me. However, you all did your best with the greatest intentions. I love animals and as much as they make me laugh, tears flow easily too.

Reminds me of my daughter's hamster, Norm. He got an infection around his eye, so half his head bulged alarmingly and eventually the eye fell out. I figured he was a goner, knowing that something like that in humans would probably spread through the optic nerve to the brain! However, wishing to keep my daughter happy that we were trying to help, I gave him some Amoxil.

When he appeared to be failing, I figured an overdose of morphine would ease his departure. By my guess, he weighed about 100g. I gave him 5mg of morphine. Scaled up to the normal 70kg male human, that would be a massive overdose of about 3500mg (i.e. about 200 times the usual dose)!

The morphine did nothing. He recovered uneventfully, sans one eye.